The Symbolism of the Bees on the Flag of Elba: Antiquity, Sovereignty, and Cultural Continuity

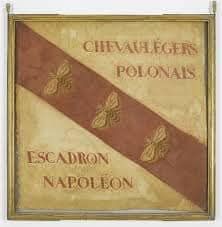

The flag of the Island of Elba, characterized by three golden bees on a white field crossed by a red diagonal band, is conventionally associated with the events of May 1814, when Napoleon Bonaparte, aboard the British ship Undaunted anchored off Portoferraio, is said to have conceived its design. However, this interpretation obscures the deeper symbolic genealogy of the emblem. The bees depicted on the flag are not generic animals but golden bees, that is, stylized representations of precious objects, whose significance derives from a long and complex tradition of political, religious, and mythological symbolism.

The immediate historical context of the emblem lies in the proclamation of Napoleon as Emperor on 18 May 1804. Rejecting dynastic legitimacy based on hereditary lineage, Napoleon sought to ground his authority in personal merit, military success, and imperial universality. This ideological stance required a symbolic system distinct from that of traditional monarchies. During deliberations on imperial insignia, several emblems were proposed, including the lion and the Gallic rooster. The lion, long associated with divine and royal power, was considered unsuitable due to its close association with English heraldry, while the rooster was dismissed as insufficiently dignified for imperial representation.

The bee was ultimately proposed by Jean-Jacques Régis de Cambacérès, Archchancellor of the Empire. The choice reflected a conception of sovereignty that was neither strictly monarchical nor republican but rather a centralized political order structured around discipline, productivity, and collective cohesion. This symbolism resonated with late Enlightenment and post-revolutionary political thought, which sought strong executive authority without recourse to traditional aristocratic legitimacy.

Beyond its modern political implications, the bee carried profound antiquarian associations. In ancient Egypt, the bee functioned as a royal and divine symbol, closely linked to kingship and cosmic order. Classical literature further reinforced this imagery: in Book IV of Virgil’s Georgics, the beehive is presented as an idealized social organism, governed by cooperation, hierarchy, and devotion to the common good. Modern archaeological and genetic research has underscored the relevance of this model by situating the origins of agriculture in the Early Neolithic period, between the eleventh and tenth millennia BCE. In this context, the bee may be interpreted as a symbolic precursor to human agricultural practice, exemplifying the collection, transformation, and productive management of natural resources.

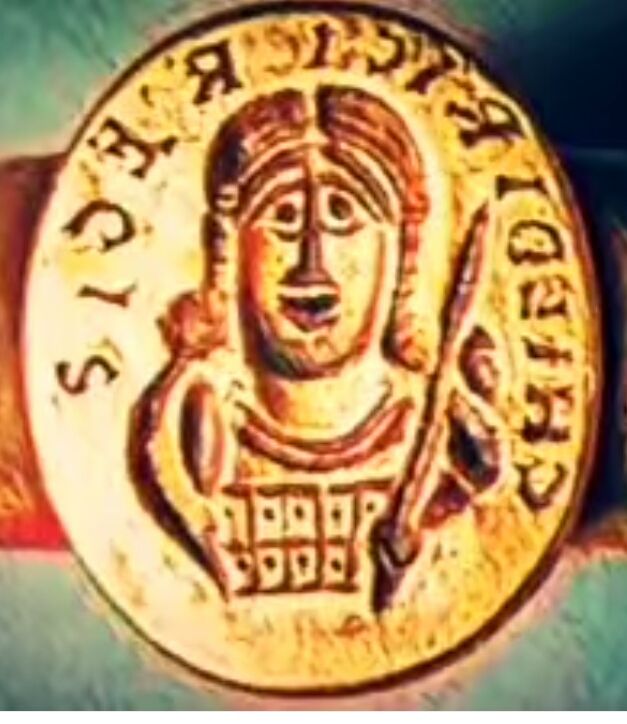

Napoleon’s adoption of the bee also drew explicitly upon early medieval precedents. On 27 May 1653, the tomb of Childeric I, king of the Franks, was discovered in Tournai. Among the grave goods were approximately three hundred golden bees or cicadas, documented in detail by Jean-Jacques Chifflet in Anastasis Childerici I (1655). Childeric, who died in 481 CE, was the last pagan Frankish king and the father of Clovis, the first Christian ruler of the Franks. The Merovingian dynasty thus represented, for Napoleon, the most ancient and symbolically potent lineage of French sovereignty, untainted by later feudal or ecclesiastical constraints.

The bee motif also appears in early modern Italian political iconography. In 1640, beneath the equestrian monument of Ferdinand I de’ Medici in Florence, Pietro Tacca created a bronze plaque adorned with ninety bees and a central queen bee, symbolizing the political unity of the Florentine territories under ducal authority. The bronze was cast from Ottoman cannons, further associating the imagery with military power and Mediterranean geopolitics, including the strategic role of Portoferraio and the Island of Elba in controlling the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Mythological and literary traditions reinforce the sacral dimension of the bee. Pausanias recounts that bees sealed the lips of the poet Pindar with wax, granting him divine inspiration, while Ethiopian tradition associates the legitimacy of kingship with recognition by bees, as in the case of King Lalibela. Renaissance esoteric literature, such as Agrippa von Nettesheim’s De Occulta Philosophia, likewise identifies bees as auspicious symbols of orderly sovereignty and obedient subjects.

Within this symbolic framework, the three golden bees of the Elban flag should be understood not as an isolated Napoleonic invention but as the culmination of a longue durée tradition linking sacred kingship, productive order, and imperial authority. Through this emblem, the Island of Elba was inscribed into a symbolic continuum extending from ancient Mediterranean cosmologies and early medieval regalia to modern imperial ideology.